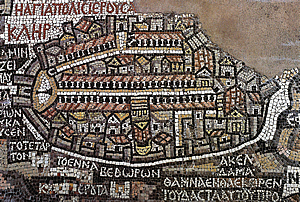

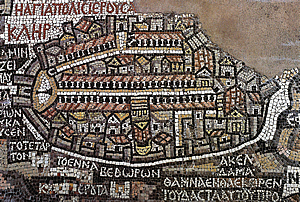

Church of St.George, Madaba, Jordan. (6th cent A.D.)

| HOME | |< | << | Chronological Table: A.D. 96 – 192 | Hadrian in Antioch: A.D. 129 – 30 | Hadrian in Palestine | Simeon bar Cochba | Hadrian in Alexandria, A.D. 130 – 1 | Alexandrian Christianity | The second Jewish war, A.D. 132 – 5 | The city of Aelia | The church in Aelia | The Jewish-Christian church | Aristo of Pella | >> |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hadrian passed through Asia and Phrygia and spent the winter of 129-30 in Antioch. It is very doubtful how much we can say about the church in Antioch at this period; it passes into relative obscurity for forty or fifty years. It is unlikely that its history was peaceful.

The heretical schools associated with the name of Satornil were directing the minds of their devotees to a purely spiritual deity outside of time and space, and a purely spiritual Christ. It is unfair, perhaps, to use words like 'unsubstantial' or 'nebulous' of this type of Christianity; no doubt its adherents felt that spirit was far more real and powerful than flesh or material substance. Their own spirituality was so intense as to lead to a denial of the bodily life, which they thought of as evil; they abstained from wine and flesh-meat; they practised celibacy. They could quote texts from Paul which seemed to support their idea of a current of spiritual power in the body so strong as to crucify the flesh and its lusts; he had said such things in Antioch (Galatians v. 24).

The same sense of the gospel as spirit and power is found, of course, in Ignatius, but it is a spirit-power which becomes flesh in Jesus Christ, and in the heart of the believer, and in the sacramental fellowship of the church; it has an affinity and affection for flesh. It is thus compatible for him with a very full participation in the catholic tradition which comes so clearly into sight in his writings; in fact it is in and through the catholic order that he has contact with spirit. Round these two conceptions the evolution of the future Syrian Catholicism seems to take place; the idea of spirit and the idea of church order. The spirit-theology of Paul and John is balanced by the ecclesiastical Gospel of Matthew, in which Peter is the leading apostle, and Jewish tradition is made available to the Gentile churches.

|38 This background material is our best guide to the nature of Antiochene Christianity at this time; and we may append to Matthew, in our consideration of it, the Didache or Teaching of the Twelve Apostles to the Gentiles, which is the first of the Syrian church orders, and yet tells us of wandering prophets and teachers so filled with Holy Spirit that it was impiety to question their words or acts. It gives us sacramental benedictions which retain a pronounced Jewish tinge, though the colour of the book as a whole is decidedly anti-Jewish. When we come to Theophilus, who was bishop of Antioch in the hundred-and-seventies, we find a theology which is quite definitely on the Jewish and biblical side, and yet it has a quiet spirituality of its own which defies definition. We get the impression, however, that the stronger, more dynamic, spirituality of Ignatius has rather given way to a liberal Law-and-Prophets Christianity based on Matthew and the Old Testament.

Can we go farther than this? Can we place in Syria, and at this period, the production of some of the ' pseudonymous' books which were issued under apostolic names? the second Epistle of Peter? his Revelation ? his Preaching ? his Gospel ? the last of which is first reported from the neighbourhood of Antioch. They affirm the authority of Peter and the Twelve; they work from the Law and the prophets; they proclaim a fiery judgement which is to come. They belong to a different school from the millennial apocalyptic of the Phrygian and Asian tradition, so that we are justified in looking for their origin elsewhere; but Alexandria is not excluded, nor Rome.

Or may we suggest 2 Clement, which uses a verse from Ignatius, and passed into the Syrian New Testament along with 1 Clement?

Eusebius preserves a list of Antiochene bishops; but only one out of the first five is anything more than a name to us. They are Euodius, Ignatius, Heron, Cornelius and Eros; then Theophilus, who was still living in 180.

top

From Antioch Hadrian passed on into Palestine and visited Jerusalem in 130. Work had already begun on the rebuilding of this city, and there was a population of some sort. It is a reasonably secure assumption that a Christian church had been established there. Hegesippus tells of a return of disciples from the church-in-exile at Pella; and another authority, quoted by Eusebius, gives the names of a number of Jewish-|39Christian bishops, who claimed succession from James the brother of the Lord though it is not said that they were of the family of Jesus. The Jerusalem elders and bishops of this period would be the official custodians of the traditions about James the Just and the other members of the family which were written down some forty or fifty years later by Hegesippus. Hegesippus was another of the younger men who were destined to play a part in the history of the Roman church. All roads led to Rome for this generation.

It was about this time, or a little earlier, that the Epistle of Barnabas must have been written, as appears from one of its scripture elucidations :

Behold they who destroyed the Temple, the same shall build it. [Isaiah xlix. 17.] It is happening [Barnabas says], for through their going to war it was destroyed by their enemies, and now they and the servants of their enemies are building it up.

(Epistle of Barnabas, xvi, 3.)

This sentence suggests a policy of co-existence and collaboration in Jerusalem which would not have been possible in the years 130-2, at the end of which a serious war broke out. It appears to belong to an earlier time when Romans and Jews were co-operating, a time which is also reflected in the legend about Aquila which we gave in full in an earlier chapter. If Hadrian had not given orders earlier for the rebuilding, either in 117 at his accession or at some later time, at any rate he did so now; but not in the spirit of co-operation suggested by the verse in Barnabas, for his decision aroused the Jews to fury. The new city was not to be a Jewish sanctuary or ethnic centre; it was to be a Roman outpost on the eastern frontier. This was a natural policy, and may be compared with the rebuilding of Carthage and Corinth by Julius Caesar. It was in line with the Romanization of many other oriental cities which were growing wealthy on the caravan trade with the far east.

The late and fragmentary character of the sources does not enable us to decide precisely what steps Hadrian took before the war, but it is clear that there was enough friction now to create a very ugly situation. The war, which broke out after the departure of Hadrian, cannot have been engineered without considerable preparation, and we read in the Talmud of numerous journeys of Rabbi Akiba into Mesopotamia, to Nisibis and Nehardaea, where there were influential groups of Jews, and also into Cilicia and Cappadocia; it is possible that the Jewish |40 communities in these border-line countries provided some assistance and support.

According to the Talmud, Hadrian had already taken severe measures. He is said to have forbidden the practice of circumcision and even the keeping of the Sabbath and the reading of the Law; but this sounds like an exaggeration.

top

The Jews seem to have restored their national organization and rural economy under the rabbinic sanhedrin, and its 'prince' or 'patriarch', Gamaliel III, whose death must have occurred about this time. Their temper was fiercely nationalistic and Zionist. They had set their hopes, with all the intense fervour of which their race is capable, on the restoration of the Jewish state, and the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem, and they were ready to fight one more desperate war to attain this purpose. They had in readiness a military leader, whose name was Simeon the son of Cosebah. The great Rabbi Akiba, now a man of very great age, proclaimed him to the nation as the promised Messiah, under the title of 'Bar Cochba', the Son of the Star, which was taken from the prophecy of Balaam, which Christians also made use of for their Messiah.

There shall come forth a star out or Jacob,

And a sceptre shall rise out of Israel ...

And Edom shall be a possession;

Seir also shall be a possession for his enemies,

And Israel shall do great acts of war.

(Numbers xxiv. 17 – 18.)

– the name of Edom, which was the country of origin of the Herod family, being often used in Jewish writings as a symbol for Rome.

We recognize in these religio-nationalistic activities the Jewish counterpart of the millennial fancies of Papias and Justin and others. The two interpretations of prophecy grew up, no doubt, side by side and in opposition to one another. The nationalist Jews dreamed of a renewed and restored Jerusalem under a military Messiah who would exercise empire over the earth. The Christians of Phrygia dreamed of a renewed and restored Jerusalem under their crucified Messiah Jesus, when he came again in glory. Both expressed their aspirations in imaginative apocalyptic language; for it was asserted, according to the |41 Talmud, that Bar Cochba blew flames of fire out of his mouth; and he seems to have set the pattern for the Antichrist of the later Christian poets and prophets; for apocalypse in the second century did not so completely lose touch with history as we would suppose if we only had the Revelation of Peter.

We have no information about the apocalyptic theology of the Jewish-Christian bishops, prophets and teachers in Israel. We only know that they refused to recognize Bar Cochba and would not take part in the war. The conflict with the national authorities passed into an acute phase and they were proscribed as heretics and very soon, no doubt, as traitors. The name of Jesus was cursed in the synagogues, and the 'Nazareans' themselves were forced to 'blaspheme Christ', as Justin tells us in his Dialogue. It is to this unhappy time that we must allot the virtual extinction of the oldest Christian churches, those that were formed among the Jews themselves.

top

We do not know whether Hadrian realized how serious the situation was in Palestine. It is unlikely that he did. At any rate he went on to Alexandria, where he passed parts of 130 and 131, giving himself up to sight-seeing and pleasure.

It was in Egypt that an event occurred which demonstrated the incompatibility which existed between the 'ethical monotheism' of Jews or Christians and even the most enlightened paganism of the day. We have mentioned a young man named Antinous who attended upon the emperor. He was drowned in the Nile, and the emperor, who had a personal attachment to him, consoled himself as best he could by building a temple in his honour where he could be worshipped as a god; a town was founded on the site and ceremonial games were held every year in his honour. Now an infatuation of an older man for a boy would cause no remark among the Greeks. Zeus, the father of Gods and men, had his Ganymede. Achilles had his Patroclus. The Symposium of Plato finds a place for it in the life of an educated man. But the deification of an emperor's personal homosexuality seems to carry a romantic view of masculine love rather far. It shocked the Christian conscience, as we see in Justin and Hegesippus and other writers of the period. Eusebius has pointed out that Hegesippus dates himself by his |42 statement that this event took place in his own time. He remarks that the pagan world was still erecting cenotaphs and temples to men,

one of whom was Antinous, the slave of Hadrianus Caesar, for whom the 'Antinoean Games' are celebrated; who lived in our own time [or, which games were instituted in our own time]; indeed the emperor founded a city and named it after Antinous, and appointed prophets.

(Hegesippus, Note-Books, in Eusebius, E.H. iv, 8, 2.)

The childhood, or possibly the youth of Hegesippus thus falls into this period, along with Irenaeus, Florinus, Polycrates and Narcissus, who were all to play their part in church history for fifty years. Hegesippus was an oriental, probably a Jewish Christian, who had close connexions with the old Jewish church in Palestine, and preserved many of its historical traditions .

In Egypt anything could happen. The old and the new kept house together. The native cults of cats and crocodiles continued to flourish and furnished the Jewish and Christian apologists with material for their more satirical passages. It was the home of Isis, the queen of heaven, the most attractive of all the mother-goddesses. It was the home of magic and mystery; and Hadrian, like many sceptics, had a weakness for the wonderful. In the midst of these mystic raptures and primitive superstitions the most modern learning had its comfortable home. It was here that Euclid had laid the foundations of the geometrical science. Eratosthenes had calculated the distance of the moon. Ptolemy was mapping out the heavens; unfortunately on a geocentric basis, though there were still those who held that the earth went round the sun. The first steam-engine had been made, or at any rate projected. The great Museum, or Institute of the Muses, was said to contain a copy of every book in the world, including the original manuscript of the Septuagint; or so at least Tertullian believed (though perhaps he had forgotten about the destruction of the old library by Julius Caesar). It has been calculated that it must have contained at least a million volumes. The principal Jewish synagogue, with thrones for its seventy or seventy-two elders, resembled a vast temple; so big it was, the Mishnah said, that an attendant had to wave a flag as a sign when the people were to say 'Amen'. In the Serapeum, the great compound god Serapis, who had been invented or imported by the first Ptolemy, was worshipped by all. In the Koreum a form of the |43 Eleusinian mysteries was celebrated, and on January 6, after a night of chant and vigil, the worshippers of Kore, 'the maiden', were shown her holy child, who was identified with 'aeon', the 'age': the new year itself, which was the offspring of endless time.

A third- or fourth-century writer in the Historia Augusta preserves a letter which Hadrian wrote during this visit to his brother-in-law Servianus, which is an excellent example of his light vein in literature. Everyone in Alexandria, he remarked, worshipped the same god:

The Egypt which you used to commend to me, my dear Servianus, I have discovered to be but lightly balanced, wavering with every motion of rumour.

topThe worshippers of Serapis are the Christians. Indeed those who call themselves' bishops of Christ' are devotees of Serapis. There is no synagogue-ruler of the Jews, no Samaritan, no elder of the Christians, who is not an astrologer, an inspector of entrails, or a watcher of the flight of birds. The patriarch himself, when he visits Egypt, is forced by some to adore Serapis, and by others to adore Christ. ...

They all have one sole deity, which is money. This is what all the Christians and all the Jews worship: and the Gentiles too.

(Scriptores Historiae Augustas, Loeb ed., vol. in, p. 398.)

It would be improper, of course, to use this lightly written document to establish the detail of church organization in Alexandria; nor should we take its picture of a financial syncretism too seriously; but the name of Christ is certainly much more prominent than we would have expected, even though it is not in the best company. It is plain that Hadrian had seen or heard gossip about the Christian bishops and elders, and had taken note of the official visits of the Jewish patriarch, Gamaliel III or some ill-fated successor – possibly even Bar Cochba himself.

We have already tried to give a sketch of the early organization of the church in Alexandria as it was seen in later legend. If these legends have any truth in them, the bishop had a position which resembled that of the patriarch; his sanhedrin of elders or bishops formed a close corporation; no deacon could aspire to the episcopate, as at Rome; the congregation or congregations can have had little power. But actually we must confess that we lack the materials to construct a reliable picture. |44 We have a list of bishops, however, with the number of years they held office, which is preserved in the pages of Eusebius. If we start in the year 62, a number obtained by working backwards from 190, the approximate date of the accession of Demetrius, we find that it works out like this: Annianus (or Hananiah) 62, Avilius 84, Cerdon 98, Primus 109, Justus 119, Eumenes 130, Marcus 143, Celadion 153, Agrippinus 167, Julian 178, and Demetrius 190. Demetrius is the first bishop about whom we have any real information. Annianus occurs in legend. The rest are mere names.

We shall return in our next chapter to the subject of the Alexandrian church. No doubt all the varieties, both Jewish and Gentile, were to be found there, and all the books were assiduously studied. Old Gospels were copied and new Gospels were written. Scholars and mystics wrote commentaries and evolved new theologies. Florinus, who had listened to Polycarp talking about John in Smyrna, may have bought a copy of Matthew or John at a bookstall. He may have met Valentinus, who studied the Johannine Gospel, and combined the wisdom of Jesus and the intellectualism of Paul in a wonderland of spiritualized mythology; a form of thinking to which Florinus himself ultimately succumbed. Basilides, the Alexandrian counterpart of the Antiochene Satornil, was fashioning a new philosophy out of the old gospel material with the help of Iranian gnosis. The Platonist Carpocrates was making strange use of Matthew. The reign of Hadrian was the flowering time of the heresies, it has been said.

The fact is that the figure of Jesus as saviour in the Pauline epistles, and the stories of his wonderful life and wise teachings as given in the Gospel according to Matthew, had come to the notice of the intellectuals. Among the courtiers of Hadrian was a certain Phlegon, a royal slave like Antinous (and very probably Florinus too), to whom he subsequently gave his freedom. Phlegon was an intellectual who wrote a number of books on history and antiquities and the wonders of the world. In one of these books he gave some account of the darkening of the sun and of the earthquake which are said to have occurred at the crucifixion. The Matthaean Gospel had come to his notice as a document which deserved serious consideration. It cannot, or course, be stated that he was with Hadrian in Palestine and Egypt at this time; but the fact shows that the interest in Christianity at the court of Hadrian was not confined to Florinus.

top

In the year 132 war broke out in Palestine, and the Jews made their last desperate attempt to regain their independence. It is pathetic to reflect how seldom, and for what brief periods, the Jews have succeeded in establishing an independent state in Jerusalem. It is a tragic history, and no episode in it is more tragic than the misguided effort in 132-5 to save the site of the holy city from desecration by the infidel and to realize the messianic dream. It was a heroic, fanatical, and hopeless effort. They had no allies, so far as we can see, and they were not supported by risings of Jews elsewhere. Yet the war dragged on for three or four years, and it cost the Romans much blood and treasure to bring it to a successful issue. No great historian, like Josephus, arose to chronicle its turns of fortune. It is a confused tale, illuminated by a few references in the historians of later times, and dimly recorded in the traditions preserved in the Talmud. The meagreness of our information blinds us to its importance.

It began, we may suppose, with fanatical guerilla fighting; and the Jews met with dramatic successes in its first phases. Bar Cochba took Jerusalem and seems to have reigned there for something like two years; for coins turn up which are marked with the names of 'Symeon the'Prince' and 'Eleazar the Priest', and such inscriptions as 'The First Year of Freedom' and 'The Second Year of Freedom'. Two of Bar Cochba's letters have been discovered among the 'Dead Sea Scrolls', which confirm the name Simon or Symeon son of Cosebah. The coins confirm the title of nasi or prince. No doubt he was waiting for God to grant complete victory before he took the title of king.

Hadrian had returned to Rome in 132, and he entrusted the conduct of the war to his prefect Tineius Rufus. The Mishnah confounds this man with Terentius Rufus, who was the Roman commander at the end of the first war under Titus; it calls him Tyrannus Rufus or Turnus Rufus the Wicked. Despite all the Roman efforts the Jews maintained their hold on the holy city and other strong points in the country, and Hadrian had to bring his best general, Julius Severus, from Britain, with strong reinforcements. In the summer of 134 he visited the country himself. Had the empire been engaged in civil strife, or in serious external war, Akiba and Bar Cochba might have been successful for a time in establishing their free Jewish state; for this has only ever been |46 done when the weakness or dissensions of the greater powers could be turned to advantage. It was not so to happen in this case.

The country was reconquered by the Romans at very great cost. The number of the Jewish casualties, as given in the Talmud, seems fantastic, but should be treated with respect; and it is clear from the Roman evidence that their armies suffered heavy losses too. They recaptured Jerusalem, however, and the Jewish leaders, with the remainder of their army, were shut up and besieged in the strong city of Bitther, the modern Khirbet-el-Yehoud, which fell in 135 after a protracted resistance in which great numbers of Jews were killed or taken prisoner, only to be subjected to the most revolting tortures or sold as slaves. Among the prisoners was Akiba himself, now a very old man; for he was said to have reached the conventional complement of a hundred and twenty years. His flesh was slowly scraped from his bones with iron combs or 'shells', a regular procedure in the Roman legal system, as we shall see in the Acts of the Christian martyrs. At the end it was evening, and the time came when the pious Jew recited the Shema, which is recognized by Jews and Christians alike as the first commandment of the Law. Akiba made a heroic effort and performed this duty. 'Hear, O Israel,' he said, 'the Lord our God, the Lord is One'; and on that last word, the tradition tells us, he expired. His crazy dream of a military theocracy, centred in Jerusalem, brought ruin to his people in his time; but his example gave them lasting inspiration, and his labours on the interpretation of the scripture and the codification of the oral law provided the Judaism of the future with a sure foundation.

Not every Rabbi shared his apocalyptic hope. 'Akiba,' said one of them, 'the grass will spring from thy jawbone, and yet the Son of David will not have come.'

top

It was on the ninth of the month of Ab that Nebuchadnezzar had entered Jerusalem in 586 B.C., and it was on the tenth day of the same Jewish month (which fluctuates between July and August), that Titus watched the temple burn in A.D. 70. It was a fatal date in the Jewish calendar. The tractate Taanit of the Mishnah, which deals with fasting, |47 and was composed not very long after this period, speaks of it as follows:

On the ninth of Ab it was decreed that our ancestors should not enter the Holy Land. On the same day the first and second Temples were destroyed, the city of Bitther was taken, and the site of the city was ploughed.

(Mishnah: Taanit, iv. 6.)

The ploughing of the site was an old Roman ceremony which was used in laying out a new city. The old Jerusalem was to be forgotten, and the day of destiny seems to have been chosen to inaugurate a new city with a new name and a new religion. Such was the policy now put into effect. It was called Aelia Capitolina; Aelia from the family name of Hadrian himself (Publius Aelius Hadrianus), and Capitolina from the great temple of the chief deity of Rome, Jupiter Capitolinus. A temple in honour of this god was erected on the site of King Solomon's Temple, and a statue of Hadrian was put up in it, so that, at long last, the emperor had succeeded in establishing himself in the place of the God of heaven. The Abomination of Desolation spoken of by Daniel the prophet stood where it ought not.

Hadrian was determined to avoid all possibility of disaffection in his new frontier city. No Jew was allowed to settle there, or even come in sight of it, though a curious privilege was allowed them as time went on. We have evidence from the fourth century that once a year, on the ninth of Ab, they were allowed to stand by the piece of the Temple wall which still remained and lament for the glory which had passed away. Even so they had to endure the mockery of the Roman soldiers and to pay bribes for the privilege.

The sanhedrin of rabbis had been dispersed, but in process of time it was reconstituted under Symeon III, the son of Gamaliel III. His court shifted from place to place, but was finally settled at Tiberias on the Sea of Galilee. The war must have weakened the hold of Judaism on the coast towns and in Palestine generally, and time was again required to recover. Thousands of Jews had been killed in battle, massacred, driven into exile, or sold as slaves. Few of the rabbinic band remained; but once again, the Mishnah says, there were five selected disciples associated with the patriarch. Among these were Simon ben Jochai, Judah ben Ilai and Rabbi Meir. Symeon III had a son named Judah, the seventh in descent from Hillel, who is known in history as |48 Judah the Holy. Rabbi Judah the Holy is said to have been born on the day that Rabbi Akiba died; he died himself about 220; and it was under his direction that the Mishnah was reduced to writing. Rabbi Meir took a leading part in the work.

Their headquarters after the war were in Tiberias in Galilee; and some old rabbinic documents may have taken form as early as this: the midrashic commentaries like Mekilta on Exodus and Siphra on Leviticus, and the early Mishnah tractates like Taanit on the fast days, and Megilloth on the books to be read in the synagogues; and Pirke Aboth, which gives the pedigree of the rabbinic fathers, with characteristic sayings of each.

top

|

| Jerusalem on the Madaba Mosaic Pilgrim Map. Church of St.George, Madaba, Jordan. (6th cent A.D.) |

It follows of necessity that the Jewish church in Jerusalem came to an end, but there may have been a thin element of continuity; for there must have been some Gentile Christians in Jerusalem before the war, and Jewish Christians may now have taken refuge in the Gentile church.

The church which existed in Aelia after the war was entirely Gentile, and therefore its episcopate was Gentile. The document used by Eusebius gave the names of fifteen bishops of the Gentile succession whose accessions have to be fitted into the fifty-five years previous to about 190. Their names are Mark, Cassian, Publius, Maximus I, Julian I, Gaius I, Symmachus, Gaius II, Julian II, Capito, Maximus II, Antoninus, Valens, Dolichianus, and finally Narcissus. We have discussed this list before and have pointed out that it must have been preserved as the title-deeds of Narcissus. Various theories have been propounded to explain why there are so many names. We suggested that the first thirteen names might be those of a newly constituted bishop with twelve elders from whom successors might be chosen. Or did Maximus and Julian and Gaius enjoy two terms of office, like Narcissus himself? Or did episcopates sometimes overlap, like those of Alexander and Narcissus? Or is the number itself insecure? Eusebius gives fifteen names in his Chronicle, but only thirteen in his History ; he omits the second Maximus and Antoninus, probably by error.

Narcissus was still living in 217 or thereabouts, and claimed at that time to be a hundred and sixteen years old, not far from the conventional hundred and twenty. We may doubt whether he remembered his age correctly; but we cannot doubt that he was a very old man, older than |49 other old men who were living at that time. He can hardly have been born later than the hundred and twenties, and his memory would easily run back into the war and post-war period. He was a Christian counterpart of Rabbi Judah the Holy.

According to the testimony of Jerome, who lived at Bethlehem in the fourth century, a temple of Aphrodite, or Venus as she was called by the Romans, was built by Hadrian's order on the site of the Crucifixion; no doubt she was equated with Ishtar or some other equivalent Syrian goddess. This temple was demolished two hundred years later by the order of the Emperor Constantine and replaced by a Christian church, which was dedicated in 335; the present church of the Holy Sepulchre stands on this site. The traditional sites of the Crucifixion and Resurrection were so close together as to be included within one range of buildings. This local tradition agrees with the statement in the Johannine Gospel which says, 'There, because it was near at hand, they laid the body of Jesus.' It was inside the walls of Aelia, and therefore of course of the modern Jerusalem: but it should be outside the walls of the old city of the time of Herod. This may quite possibly be the case; but the line of the old wall is not known.

Jerome also states that the cave in which Christ was said to have been born had been surmounted by a shrine of Adonis, which was a title of the Syrian god Tammuz. It is not said in the Gospels that Christ was born in a cave, but the idea was established in the tradition before the war; for Justin speaks of the cave of the nativity at Bethlehem, which was thirty-five furlongs from Jerusalem, an exact measurement which suggests local knowledge. The cave is mentioned as a place of historic interest by Origen.

Another monument was the upright stone by the site of the Temple which marked the site of the martyrdom of James the Just, and is mentioned by Hegesippus in the story of his passion. The time came when the chair of James was also shown. No doubt it was simply the episcopal throne of the Jerusalem bishops, and may have been as old as the time of Narcissus. Eusebius himself had seen it. It is noteworthy that the Gentile succession at Aelia regarded itself as the heir of the old Jewish succession, and kept alive the historic traditions.

top

We have included this half-legendary material for what it may be worth. It seems to represent the historical tradition of the church at Aelia at the close of the century. There are hard critics, of course, who dismiss it all as imagination or fabrication; but this seems too strong a procedure. It is of equal value with the information preserved in the Mishnah, and if it were a fabrication, it is not unreasonable to suppose that it would have been made rather more impressive. It does not, of course, amount to direct evidence; but the lack of direct evidence, either Jewish or Christian, must not blind us to the importance of the events of this period, and the continued importance of Jewish Christianity as a factor in eastern church history. Its work was not yet done, though its pride and its glory had disappeared and its congregations were few and scattered.

The story of Jewish Christianity since the death of Symeon in 104-7 had been a story of disintegration under the pressure of persecution and heresy; and this process must have been accelerated by the events of 131-5. It was entering into its last phase, though it still had a contribution to make.

We can make out, to a certain degree, the geographical distribution of Jewish Christianity subsequent to 135. Jewish Christians were carried east and west in the drift of displaced persons which followed the Bar Cochba war. We find an interesting group of Jewish refugees in Ephesus who discuss the problem with Justin Martyr. The legends of Edessa suggest that others reached the Syrian principalities of the far east; the Christian missions to the far east cannot be placed any later than this. Nearer Palestine, on the River Orontes, which flows down to the sea below Antioch, there was a community of Elkhasaite Christians at Apamea, which sent a mission to Rome in the early third century; and there was a community of Nazareans at Beroea, the modern Aleppo, which was still flourishing in the fourth century. In Cappadocia, a Roman border-province, there were Greek-speaking Jewish Christians of the Ebionite type, who actually produced their own translation of the Old Testament towards the end of the century. There was a sophisticated Hellenistic Ebionism in the cities of the Phoenician sea-coast, which produced the legends about Clement and Peter and their conflicts with Simon of Samaria. There must have been a considerable |51 Jewish-Christian expansion to produce all this evangelistic and literary activity.

Apart from these developments or offshoots of the original Jewish-Christian church, there were still the old communities round the Sea of Galilee, at Nazareth, Pella, Cochabha and other villages. Here was to be found the older Jewish Christianity, with its episcopal successions in the family of Jesus, its Hebrew or Aramaic gospel, its tolerance of Paul, and its not unfriendly relations with the Gentiles. Hegesippus, who arrived in Rome in the hundred-and-fifties or sixties, seems to have represented this kind of Palestinian Christianity.

The civilization of the west was making progress in this country, and the Greek language was more necessary than ever for purposes of business and administration, as well as for learning and literature. It would appear that the Jewish-Christian patriarchate at Pella was bilingual, and that its theological schools made use of the Septuagint, and published their learned works in Greek. By this means at any rate they could maintain relations with oecumenical Christianity.

top

In the period immediately after the war the church at Pella had a distinguished scholar named Aristo, who wrote a book called the Dialogue of Jason and Papiscus, the first Christian book in dialogue form. It was well known in the Greek-speaking churches, since it was singled out for attack by the philosopher Celsus about thirty years later, and was defended early in the third century by the Christian scholar Origen. Neither of them mention the name of the author, but this is vouched for by another Celsus, who translated it into Latin in the seventh century, so that it had a long life of usefulness in the church. Origen tells us that it was in the form of a debate between a Jewish Christian and a Jew of Alexandria on the subject of the Old Testament prophecies and their fulfilment in Christianity. He praises the author because he allows the Jewish debater to acquit himself nobly and worthily. The seventh-century Celsus says that he was convinced of the truth of Christianity and accepted baptism.

Eusebius made use of the writings of Aristo for information about the Jewish war; and the following paragraph is taken in whole or in |52 part from one of his books and therefore gives us the evidence of a contemporary Jewish Christian.

The war came to a climax in the eighteenth year of die rule of Hadrian [A.D. 135] at Bith-thera, a city of great strength, which was not a very great distance from Jerusalem. The siege went on for a very long time. The rebels were brought to utter destruction by hunger and thirst; and the man who was guilty of the folly paid the just penalty. After this the whole nation was forbidden ever to set foot in the country round Jerusalem, by a legal decree, and by commands of Hadrian, and not even to gaze from a distance on the soil of their fatherland. So Aristo of Pella relates.

(Eusebius, E.H. iv, 6, 3.)

Eusebius does not name the book of Aristo from which he quotes; but it is quite probably the Dialogue ; for the defeat of Bar Cochba was hailed by the Christian schools as a new fulfilment of prophecy which confirmed all the rest. 'Your land is desolate', they quoted from Isaiah;' As for your country, strangers devour it before your eyes'; and even more aptly, 'Your eyes shall see the land from far away.' These texts appear henceforth in the Christian 'testimony' books, and it is thought probable that Jason and Papiscus inspired this whole series of anti-Jewish compositions, many of which were composed in dialogue form.

Very few quotations from Aristo have come down to us, but, such as they are, they show that his theology was not out of line with that which prevailed in the Gentile churches. Christ was the pre-existent Son, by whom God created the heaven and the earth; he was the 'Beginning' which is spoken of in the first verse of Genesis (see Col.i.18, etc.). It is an important historical fact that the old Jewish church at Pella had a scholar who could write in Greek in a manner which was acceptable to the church at large. The Jewish Christians were not all Ebionites in the narrower sense of the word; even the oldest Jewish Christianity prior to 70 A.D. was probably bilingual and had its Hellenistic wing. It is no more extraordinary for a Jew like Aristo to write in Greek, than for a Roman like Hermas, or a Phrygian like Papias or Epictetus.

It is a great loss to the historian that he does not possess the Apology of Quadratus, the Interpretations of Papias, or the Dialogue of Aristo; for they are the first Christian books composed in the Greek style by men who appeared as authors and used their own names. They belong

|53 to three different lines of thought. Athens gives the first approach to the Hellenistic world; Phrygia gives the first mystical interpretations of the prophets and evangelists within the fellowship; Palestine gives the first approach to the Jews. We have some notion of each, as it happens; and Papias is not badly represented in allusions and quotations; but we would like to be able to read them for ourselves and form our own impressions. They are the forerunners of a catholic theology.

<< | top | >>